Labour Party History Part II: Corbynism

After Ed Miliband’s controversial victory in the leadership contest of 2010, Labour made some key changes to the party rules before the 2015 contest. Namely, the party moved to a one member, one vote system where, well, each member got one vote. MPs and unions now had just as much voting power as someone who paid £3 online to get to vote.

Initially, Labour’s hard-left faction wasn’t expected to do well in the 2015 contest. In 2010, leftist Diane Abbott had come in fifth out of five candidates. However, after Jeremy Corbyn entered the race, Labour saw a massive upswell in party membership. These new, Corbyn-supporting members tended to be people who felt left behind by their peers in society. Thanks to the rule changes, fee-paying party members were able to easily elect Corbyn despite the fact that most MPs did not support his candidacy.

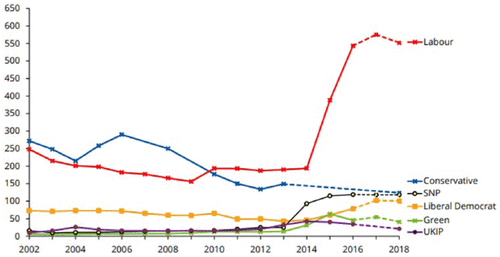

These numbers shows membership figures(in the thousands) of British political parties. It’s hard to overstate the effect that Jeremy Corbyn had on Labour’s numbers.

Unfortunately for Corbyn, Labour members comprised less than 1% of the British electorate in 2015. Even though he was popular within Labour, Corbyn’s hard-left political views had his public approval rating at -41 in December 2015. With these numbers, it was going to be nearly impossible for Labour to win an election. Consequently, Labour MPs forced another leadership election in 2016 that Corbyn, again, won easily.

Labour’s polling numbers under Corbyn became so bad that the party trailed the Conservatives by 21 points (44% to 23%) in mid-April 2017. Naturally, Prime Minister Theresa May decided this would be a great time to call a snap election and increase the size of her Conservative majority in Parliament. However, May ran a poor campaign beset by gaffes and a strange decision not to participate in any of the election debates. Meanwhile, Corbyn looked good in a May 31st debate simply by showing up.

In addition to May’s mistakes, Corbyn also benefited in the election from Labour’s vague, noncommittal stance about the type of Brexit deal that Britain should pursue. It allowed the party to gain the votes of committed Leavers at a time when many Remainers also saw Labour as the best electoral option. For center-left Remainers, even if they didn’t like Corbyn that much, voting Labour was usually the best tactical option to try to keep the Tories (Conservatives) out of office.

Additionally, Labour’s main competition for these sorts of voters, the Lib Dems, proved to be ineffectual. Many people were still angry at the party for breaking promises in the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition government of 2010-2015. (Some still are.) A number of voters were also uncomfortable with the highly religious Lib Dem party leader, Tim Farron, since his personal positions on the morality of abortion and homosexuality were unclear. As a consequence, Labour did not have to try too hard to win the votes of many pro-Europeans.

Labour’s vague Brexit policy was a result of the divergent views between Corbyn and the rest of his party. (I am going into detail now, as this will become important later.) While most Labour members in 2017 supported a moderate Brexit that would’ve seen the UK continue to follow most EU rules in exchange for market access, Corbyn did not want to commit to abiding by the Union’s rules on state aid. These rules prohibit national governments from using state resources to give their industries a competitive advantage, which is exactly what Corbyn wanted the British government to do.

Because of the weakness of his opponents, Corbyn started to look better and better by contrast, and suddenly his approval ratings were not too bad. In a turn that no one had expected before the campaign, Labour managed to win 40% of the vote (just 2.4 percentage points behind the Tories) and 30 more seats than in 2015. While Corbyn didn’t win the election, he crushed the expectations game, giving him the confidence to soldier on as Labour leader.

Unfortunately for Corbyn, the Lib Dems got rid of Farron and replaced him with Vince Cable, a man without controversial religious views. As time went on, the Lib Dem proposal for a second Brexit referendum started to seem eminently reasonable to Remain supporters. Time also helped the Lib Dems distance themselves from their unpopular coalition government. Suddenly, Labour faced a serious pro-European challenge, and the Lib Dems managed to momentarily overtake Labour in the polls in late May 2019.

In response, Corbyn amended Labour’s position on Brexit in favor of a second referendum, but it was too late to undo all of the damage caused by Labour’s previous ambiguity on the matter. Because some Remainers did not trust Corbyn’s past Euroskepticism, it became clear that Labour was going to have a much lower vote share in the next election than in 2017. When this election occurred in December 2019, the Leave vote was concentrated in the Conservative party (who won 43.6%) while the Remain vote was fractured among multiple parties. (Labour won 32.2%.) Because Britain uses first-past-the-post for its elections, which disproportionately favors the largest parties, the Conservatives won over 56% of the seats. As a result, Corbyn promptly resigned.

In the 2020 Labour leadership contest, Rebecca Long-Bailey emerged as the Corbynite candidate. However, she was only able to amass 27.6% of the vote, as the party’s hard-left was likely discouraged by their two consecutive general election defeats. Instead, Keir Starmer, a pro-European social democrat, emerged victorious. Starmer, a lawyer, is expected to move Labour in a more pragmatic direction. He has a reputation for having a somewhat boring personality, but some people are attracted to this quality in contrast to the unpredictable current Prime Minister and Conservative leader, Boris Johnson.